In general, this is a wonderful post and I have much to agree with here.

I'd like to tackle the following:

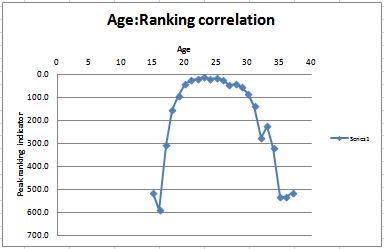

I have a few of graphs on this.

The first is based on computer rankings in the open era. The data set is all men who won a slam and were born in 1950 or later (so that most of their careers are captured in the rankings). What the graph shows is the average computer ranking of all men in the data set. The peak in this graph is around 23 to 25. The attack is quite sharp to age 20, but the taper to age 31 or so is fairly gradual. It certainly illustrates that prime age is from 20 to 29-30. (Incidentally, the small hiccup at age 24 is almost totally due to Pat Cash's crash at that age, and the one at 27 to Del Potro.)

The second graph shows just the end of year rankings for the most recent 6 top men who were multi-year #1's, and had reasonably long careers (note that Sampras has the shortest career of this group). For Laver and Rosewall, rankings before 1973 are subjective, but use my majority opinion approach. All rankings after 1973 are computer rankings (so Connors, rightly or wrongly gets #1 for 1974-78).

In this graph the peak is at 26 or 27 when no one is ranked below #2.

The next graph (and more to GD's point) is the number of majors won at each age by top major winners throughout tennis history. It includes all who won 4 majors or more, plus Murray and Wawrinka. 'Majors' include all Wim and USC/O, AO, RG since 1925, ITF majors (1912-24), and pro-majors (Wem, FrPro, USPro for the years universally recognized). Specifically, this includes: Renshaw, Sears, RDoherty, Larned, Wrenn, HDoherty, Wilding, Tilden, Johnston, Kozeluh, Borotra, Cochet, Richards, LaCoste, Crawford, Perry, Nusslein, Vines, Budge, Parker, Riggs, Kramer, Sedgman, Gonzales, Trabert, Rosewall, Hoad, Cooper, Emerson, Santana, Laver, Newcombe, Connors, Borg, Vilas, McEnroe, Lendl, Wilander, Becker, Edberg, Sampras, Courier, Agassi, Federer, Nadal, Djokovic, Murray, Wawrinka.

The red line represents the total number of titles won by this group at each age. The blue line is the two-year average for each age. This blue line tends to smooth out the line a bit to make the trend more visible. It seems that the longterm average peak major-winning age has been 24.

To see if there was a difference with modern times, I looked at just those who had won 6 or more slams in the open era (Connors, Borg, McEnroe, Lendl, Wilander, Edberg, Becker, Agassi, Sampras, Federer, Nadal, Djokovic). It looks like the peak is still about age 24.